Historical background

It is important, when considering Thomas Müntzer's life and works, to remember that he was a man born into an era of great upheaval. Economic and social changes had been spreading over Europe since the 14th century, and sporadic lower-class unrest had manifested itself in several parts of the continent - most recently before Germany, in Bohemia at the time of the Hussite Reformation. Fundamental alterations were taking place in the way in which trade and manufacturing were arranged, with money-transactions beginning to replace traditional relationships between master and worker.

All of these changes triggered profound unrest in the minds of academics, towns-people and simple peasants alike. In Germany, many considered their era - around 1500 - to be "the end of time", and fully expected an apocalyptic event. Right on cue, in the 1520s, the Ottoman armies under Suleiman the Magnificent began to conquer major parts of south-eastern Europe, and many in Germany and Austria were just waiting to be overwhelmed by the Antichrist. It was against this background that the Roman Church came under fire, and radical ideas for change burst forth, strange and new reflections of underlying social, political and economic expectations. Remember that this was the time, not only of Luther, but also of Erasmus of Rotterdam and fellow-Humanists, of the alchemists Paracelsus and Cornelius Agrippa.

The social upheavals triggered the Reformation - or more precisely, 'the reformations', for it was above all a time of massive dissent, and indeed dissent from dissent; the reformation of thought triggered further social and political upheavals.

Should you require some superficial insight into the complex geography and the myriad rulers of 16th century Thuringia,

please click here...

Birth, Family and Education

Thomas Müntzer was born in late 1489 (21 December?) or early 1490, in the small town of Stolberg in the Harz Mountains of Germany. The legend that his father had been cruelly executed by the feudal authorities has long since been shown sadly untrue. In fact, there is every reason to believe that Thomas had a fairly comfortable background and upbringing - as evidenced by his lengthy education. Both his parents were still alive in 1520, his mother dying at around that time, leading to some disagreement between Thomas and his father in 1521, on the subject of his mother's rather meagre bequests.

The Müntzer name was known in Stolberg since the 15th century, and various branches of the family were scattered around neighbouring towns and villages. The name would suggest that at some point, ancestors were minters of coins, but this may or may not have been his father's trade. The family probably moved soon after 1490 to the neighbouring and slightly larger town of Quedlinburg, and it was as 'Thomas Munczer de Quedlinburgk' that we next have sight of him, in the university records of Leipzig in 1506. Here he may have studied the Arts or even Theology: alas, Thomas never seems to have actually graduated from Leipzig. But he seems to have made up for that omission by enrolling at the Viadriana University of Frankfurt an der Oder six years later, in 1512. It is not very certain what degrees he may have obtained - almost certainly a Bachelor's degree in Theology and/or the Arts, and possibly - but less certainly - a Master of the Arts. The relevant records are full of holes, or are completely missing. At some time in this rather obscure period of his life, possibly before and during his studies at Frankfurt, he held down posts as an assistant teacher in schools in Halle and Aschersleben, at which time, according to his final confession, he is alleged to have formed a "league" against the incumbent Archbishop of Magdeburg - to what end the league was formed, other than to justify his confessors, is wholly unknown.

Early employment

Things finally become a little clearer in May of 1514, when he takes up a post as priest in the town of Braunschweig (Brunswick), where he was occupied on and off for the next few years. It was here that he really began to question the practices of the Roman Catholic Church, and to criticise - for example - the selling of indulgences. In letters of this time, he is already being addressed by friends as a 'Castigator of Unrighteousness', so obviously he had made his opinions known. Between 1515 and 1516, he also managed to find a job as schoolmaster at a nunnery at Frose, near Aschersleben, where he taught the inmates as well as children from Braunschweig.

Contact with Luther

In the autumn of 1517, he was in Wittenberg, studying and seeking a job. Here he met with Luther and became deeply involved in the great discussions which preceded the posting of Luther's Theses. We know he attended lectures at the university there, and he would have been exposed to Luther's ideas as well as other ideas originating with the Humanists, among whom could also be counted Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, who later became a radical opponent of Luther. He remained in Wittenberg for more than a year, but his residence there was broken frequently by journeys to towns in Thuringia and Franconia, always seeking employment. He continued to be paid for his position at Braunschweig until April of 1519, when he turned up in the town of Jüterbog, north-east of Wittenberg, where he had been asked to stand in for the preacher Franz Günther.

Günther had already been preaching a reformed gospel, but had found himself viciously attacked by the local Franciscans; requesting leave of absence (probably an early form of professional stress), he left the scene and Müntzer was sent in. The latter picked up where the former had left off, and with added vim. Before long, the local ecclesiastics were complaining bitterly about Müntzer's heretical 'articles' which challenged both church teaching and church institutions.

By this time, Müntzer was not merely following Luther's teachings; he had already begun to read the teachings of the mystics Suso and Tauler, was seriously wondering about the possibility of enlightenment through dreams and visions, had thoroughly explored the early history of the Christian Church, and was in contact with other, more radical, reformers such as Karlstadt.

In June 1519, Müntzer attended a disputation in Leipzig, between the reformers of Wittenberg (Luther, Melanchthon and Karlstadt) and the Roman Church hierarchy, represented by Johann Eck. This was one of the high points of the early Reformation, and our Thomas did not go unnoticed by Luther, who recommended him to a temporary post in the town of Zwickau. However, at the end of that year, he was closeted away in a nunnery at Beuditz, near Weissenfels. He probably spent the entire winter devouring books by the mystics, the Humanists and the early historians of the Church.

Zwickau

In May of 1520, Müntzer was able to follow up the recommendation made by Luther a year earlier, and stood in as temporary replacement for a reformist/humanist preacher named Johann Sylvanus Egranus at St Mary's Church in the busy town of Zwickau (population at that time ca. 7000), near the border with Bohemia. Zwickau was bang in the middle of the important iron- and silver-mining area of the Erzgebirge, and was also home to a significant number of plebeians, primarily weavers. Money from the mining operations, and from the commercial boom which mining generated, had infiltrated the town. This led to an increasing division between rich and poor citizens, and a parallel consolidation of larger manufacturers over small-scale craftsmen. Social tensions ran high. It was a town which, although exceptional for the times, nurtured conditions which presaged the trajectory of many towns over the following two centuries.

At St Mary's, Müntzer simply carried on as he had started in Jüterbog, which of course brought him into conflict with the representatives of the established Church. He still regarded himself as a follower of Luther, however, and as such he retained the support of the town council. So much so, in fact that, when Egranus returned to post at the end of September 1520, the town council appointed Müntzer to a permanent post at St Katharine's Church. He had at last found himself a proper job.

St Katharine's was very much the church of the weavers. And not just any weavers. There was already in Zwickau a reform movement inspired by the Hussite Reformation of the 15th century, especially in its radical, apocalyptic Taborite flavour.

Amongst the weavers this movement was particularly strong. Taboritism, and also spiritualism. One Nikolaus Storch was active here, a self-taught radical who placed every confidence in spiritual revelation through dreams. Soon he and Müntzer were eyeing each other up as likely allies. In the following months, Müntzer found himself more and more at odds with Egranus, the nominal representative of the Wittenberg movement, and increasingly embroiled in all manner of uproar against the local Catholic priests. The town council became nervous at what was going on at St Katharine's, and on 16 April 1521 at last decided that enough was enough: Müntzer was dismissed from his post and was forced to leave Zwickau.

As a footnote to this episode, Storch and several of his followers made their way to Wittenberg in December 1521: Luther was at that time absent, tucked away safe from the Imperial wrath in the castle at Wartburg; Storch was received by an interested Melanchthon, Luther's right-hand man, who was quite prepared to be convinced of the authenticity of Storch's beliefs. Only some stern reminders from the Wartburg preserved Melanchthon from an historical faux pas. But it is worthy of note that Apocalyptic fears and enthusiasms pervaded much of the reform movement at that time: anything, including visitations by angels and divine prophecy, was possible. And Wittenberg was caught up in such hopes and fears.

Prague

An initial scouting expedition took Müntzer over the border into Bohemia to the town of Zatec (Saaz) - this town was known as one of the five "safe citadels" of the radical Taborites of Bohemia. However, Müntzer decided that his next port of call would be Prague. It was in Prague that the Hussite Reformed Church was already firmly established and here, no doubt, that Thomas thought to find a safe haven where he could develop his increasingly un-Lutheran ideas. Possibly not far from his thoughts was the fact that, in that summer, the Ottoman armies were moving steadily through Hungary - thereby signalling the End of Time. He arrived in Prague in late June of 1521. He was made welcome since he was perceived to be what he was not - a follower of Luther - and was allowed to preach and to give lectures at the University. He also found the time to prepare a summary of his own beliefs, which appeared in what became known as the

`Prague Manifesto'. This document exists in four forms - one in Czech, one in Latin, two in German; one of them is written on a large piece of paper, about 50cm square, like a poster. It is almost certain that

none of the four items was ever published or posted in any shape or form. But it is clear from this document just how far he had diverged from the road of the Wittenberg reformers, and how much he believed that the reform movement was something apocalyptic in nature.

In early December 1521, having discovered that Müntzer was not at all what they expected, the Prague authorities ran him out of town.

The next twelve months were spent wandering: he turns up in Lochau, Wittenberg, Stolberg, Nordhausem and Weimar, applying desperately for suitable posts, but failing to be appointed.

Allstedt

From December 1522 until March in 1523, he found employment at a Cistercian nunnery (Glaucha) just outside Halle . Here he found little opportunity to continue with his reforms, despite the existence of a strong and militant local reform movement; his one attempt to break the rules, by delivering the communion 'in both kinds' to a noblewoman named Felicitas von Selmnitz probably led directly to his dismissal.

Surprisingly, perhaps, his next post was both relatively permanent and productive. At the end of March 1523, probably through the patronage of Selmenitz, he was appointed as preacher at St John's Church in Allstedt. He found himself working alongside another reformer, Simon Haferitz who preached at the church of St Wigberti. The town of Allstedt was small, barely more than a large village (pop. 600), with an imposing castle set on the hill above it.

It was the Elector Friedrich himself who held the right to appoint to St John's, but the town-council either forgot to inform him, or did not feel his approval was necessary. Almost immediately on arrival, Müntzer was busy preaching his version of the reformed doctrines, and translating the standard

church services and

mass into German. Such was the popularity of his preaching, and the novelty of hearing the services being held in German, that people from the surrounding countryside and towns were soon flocking to Allstedt - some reports suggest that upwards of two thousand people were on the move every Sunday.

Within weeks, Luther got to hear of this and he was soon writing to the local tax-collector, Hans Zeiss, asking him to persuade Müntzer to come to Wittenberg for closer inspection. Müntzer refused to go. He was far too busy carrying through his Reformation and wanted no discussion 'behind closed doors'. As part of his reforms, perhaps, he married Ottilie von Gersen, a former nun; in the Spring of 1524, Ottilie gave birth to a son.

It was not only Luther who was concerned. For perfectly good reasons, the Catholic Count Ernst von Mansfeld had spent the summer of 1523 trying to prevent his own subjects from attending the reformed services in Allstedt. Müntzer felt secure enough in his post to pen

a letter to the Count in September, ordering him to leave off his tyranny and threatening to deal with him 'worse than Luther with the Pope'.

Throughout the balance of 1523, and into 1524, Müntzer was employed in consolidating his reformed services and teachings in the small town. He also found the time to arrange for the printing of his German Church Service and two tracts, the

Protestation or Petition by Thomas Müntzer from Stolberg in the Harz Mountains, now Pastor of Allstedt, about his teachings, beginning with true Christian faith and baptism and

On Fraudulent Faith, in which he set out his doctrine that the true faith came from inner spiritual suffering and despair.

In March of 1524, matters came to a head. Followers of Müntzer burned down a small chapel at Mallerbach, much to the annoyance of the abbess of the Naundorf nunnery. The town-council and the tax-collector failed to do anything about this outrage. By June, however, the feudal authorities were beginning to get a grip and started to clamp down on the situation. In response, the people of Allstedt began to organise and arm themselves. In July, Müntzer came before the Electoral Duke Johann in Allstedt Castle, possibly in lieu of a belated 'trial sermon' for his post at St John's, and preached his famous

sermon on the Second Chapter of the Book of Daniel - a barely-concealed warning to the princes that they should pitch in with the Allstedt reforms or face the wrath of God. The reaction of the princes is not documented, but Luther went ballistic: he published his

Letter to the Princes of Saxony concerning the Rebellious Spirit demanding the radical's banishment from Saxony. Rather tamely, the Ernestine princes simply summoned all the relevant persons of Allstedt, Müntzer included, to a hearing at Weimar, where they were interrogated separately, then warned about their future conduct. This hearing had, however, the desired effect upon town-council and tax-collector, who back-pedalled rapidly and withdrew their support for the radicals.

In the night of 7th August 1524, Müntzer slipped out of Allstedt (by necessity abandoning wife and son, who were only able to join him later), and headed for the Imperial Free City of Mühlhausen, around forty miles to the south-west.

Mühlhausen (first residence)

Mühlhausen was a town with a population of 8500. During 1523 social tensions which had been brewing for several years came to a head, and the inhabitants had managed to wrest some political concessions from the elitist town-council; building on this success, the radical reform movement kept up the pressure, under the leadership of a lay-preacher named Heinrich Pfeiffer, who had been denouncing the practices of the old Church from the pulpit of St Nikolaus Church. Thus, before Müntzer arrived here, there was already considerable tension in the air. This, however, did not stop Müntzer from doing what he did best - preaching, agitating and publishing inflammatory pamphlets against Luther. His comrade-in-arms here was Pfeiffer; while the two men did not necessarily share identical beliefs, there was enough common-ground in the matter of reformatory zeal and belief in the living divine spirit to allow them to work together closely. A miniature coup took place in late September 1524, as a result of which leading members of the town-council fled the town, taking with them the city insignia and the municipal horse. But the coup was short-lived - partly because of divisions within the reformers inside the town, and partly because the peasantry in the surrounding countryside took issue with the 'unchristian behaviour' of the radicals. After only seven weeks in the town, on 27th September, Müntzer was forced to abandon wife and child once more and escape to a safer haven.

Nürnberg and South-West Germany

He went first, by circuitous route, to Nürnberg in the south, where he arranged, through third-parties, the publication of his anti-Lutheran pamphlet

A Highly Provoked Speech of Defence and Answer to the Spiritless Easy-Living Flesh in Wittenberg, as well as one entitled

Explicit Exposure of the False Belief - both of which, unfortunately, were confiscated by the city authorities before too many copies could be distributed. Müntzer himself lay low in Nürnberg, considering that his best strategy would be to get into print, rather than end up in prison. He remained here until late November and then left for the south-west of Germany and Switzerland, where peasants and plebeians were organising themselves for the great 'Peasant War' of 1524/25 in defiance of their feudal overlords. There is no direct evidence of what Müntzer did in this part of the world, but almost certainly he would have come in contact with leading members of the various rebel conspiracies; it is proposed that he met the later Anabaptist leader, Balthasar Hubmaier in Waldshut, and it is known that he was in Basel in December, where he met the Zwinglian reformer Oecolampadius, and may also have met the Swiss Anabaptist Conrad Grebel there. He spent several weeks in the Klettgau area, and there is some evidence to suggest that he helped the peasants to formulate their grievances. While the famous 'Twelve Articles' of the Swabian peasants were certainly

not composed by Müntzer, at least one important supporting document, the

Constitutional Draft (Verfassungsentwurf), may well have originated with him. In any event, it is probable that what he saw taking place here - peasants on the march, demands for democracy - inspired him to return to his old stomping-ground and set the cause afoot once more.

Mühlhausen (second residence)

In mid-February of 1525, therefore, he arrived back in Mühlhausen (via Fulda, where he was briefly arrested and then - unrecognised - released) and took over the pulpit at St Mary's Church; it must be said that the town-council neither gave, nor was asked for, permission to make this appointment - it would seem that a popular vote thrust Müntzer into the pulpit. No sooner back than he and Pfeiffer - who had managed to return to the town some three months earlier - were to be found at the centre of considerable activity. In the middle of March, the citizens were called upon to elect an 'Eternal Council' which was to replace the existing town-council, but whose duties went far beyond the merely municipal. Surprisingly, neither Pfeiffer nor Müntzer were admitted to the new council, nor to its meetings. Possibly because of this, Müntzer then founded the 'Eternal League of God', in late March (nb. some researchers date this League to late September 1524). This was in effect an armed militia, designed not just as a defence-league, but also as a God-fearing cadre for the coming apocalypse. It met under a huge white banner which had been prepared, painted with a rainbow and decorated with the words 'The Word of God will endure forever'. In the surrounding countryside and neighbouring small towns, the events in Mühlhausen found a ready echo, for the peasantry and the urban poor had had news of the great uprising in south-west Germany, and many were ready to join in.

By late April, all of Thuringia was up in arms, with peasant and plebeian troops from various district on the march.

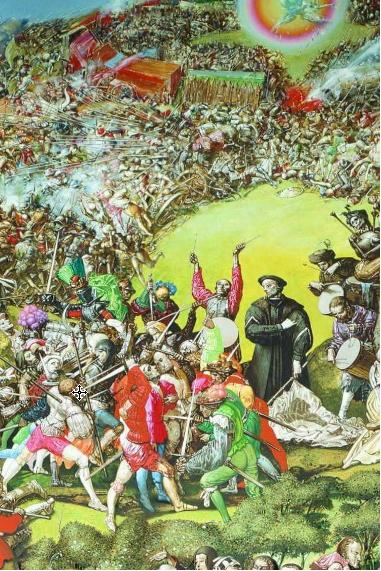

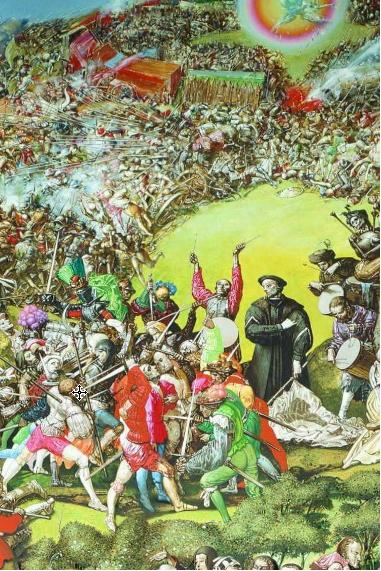

At that time too, however, the princes were laying their own plans for the suppression of the revolt. Unfortunately, the feudal authorities had far better arms and far greater discipline than their subjects. At the beginning of May, the peasant-plebeian rebels marched around the countryside in north Thuringia, but failed signally to meet up in any sensible way with other troops, being content to loot and pillage locally.

One should note that Luther pitched into all of this very firmly on the side of the princes; he made a tour of southern Saxony - Stolberg, Nordhausen, and the Mansfeld district - in an attempt to dissuade the rebels from action; in some of these places he was roundly heckled. He followed this up with his pamphlet

Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, with timing that could not have been more ill-judged - it was the peasantry who at that time died in their thousands - some estimates put it at 75,000 or more - at the hands of the princely armies.

At length, on 11th May, Müntzer and what remained of his troops arrived at the town of Frankenhausen, meeting up with rebels there who had been asking for help for some time. No sooner had they set up camp - disastrously, on a hill that would offer no escape - than the feudal army arrived, having already crushed the rebellion in southern Thuringia. On 15th May, battle was joined. It lasted barely a few minutes, and left the streams of the hill running with blood. 6000 rebels were mown down. Müntzer fled, but was captured as he hid in a house in Frankenhausen: ironically, his habit of carrying around a satchelful of copies of his letters - which has been so valuable for posterity - is what revealed his identity. On 27th May, after due torture and

confession, he was executed, alongside Pfeiffer, outside the walls of Mühlhausen, their heads being displayed prominently for years to come, as a warning to others.

Aftermath and heritage

These others, however, were not always warned. During the last two years of his life, Müntzer had come into contact with a number of other rebellious spirits - prominent amongst them were Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Melchior Rinck, Hans Römer and Balthasar Hubmaier: all of them, leaders of the nascent Anabaptist movement, which nurtured similar radical reform doctrines to those of Müntzer himself. While it is not appropriate to claim that they were all or consistently 'Müntzerites', it is reasonable to suggest that they all took on board some of his teaching. Even within the towns where Müntzer had been active, his reformed liturgies were still being used some ten years after his death, much to Luther's horror. Through the Anabaptists, a line leads from Müntzer to the extraordinary 'Kingdom of Münster' in North Germany in 1535, to the Dutch Anabaptists, to the English radicals of the mid-17th century, and beyond. It is not far-fetched to claim that Müntzer was the giant on whose shoulders other giants then stood, in a line stretching down across centuries to the socialists of the 19th and 20th centuries: it was thus that Engels and Kautsky claimed him as a precursor of the revolutionaries of more modern times. But it is not solely as an early social revolutionary that Müntzer has historical importance; his activities within the early Reformation church were - although Luther would have been the last to admit it - highly influential on the course which Luther subsequently took for his reforms.

Ottilie von Gersen (Müntzer's wife)

A brief word on Müntzer's wife, Ottilie von Gersen.

Very little is known about her, other than the fact that she was a nun who had left a nunnery under the influence of the Reformation movement. Her family name may have been 'von Görschen'. She may have been one of a group of sixteen nuns who left the convent at Wiederstedt, some miles north of Allstedt, of whom eleven found refuge in Allstedt. Apart from the son born to her and Müntzer on Easter Day, 1524, it is possible she was again pregnant at the time of her husband's death - by which time also, the son may have died. A letter she wrote to Duke Georg on 19th August 1525, pleading for the chance to recover her belongings from Mühlhausen, went unheeded, and she then disappeared into the shadows.

Ottilie has inspired a number of plays and novels over the years - look for them in the

Bibliography...

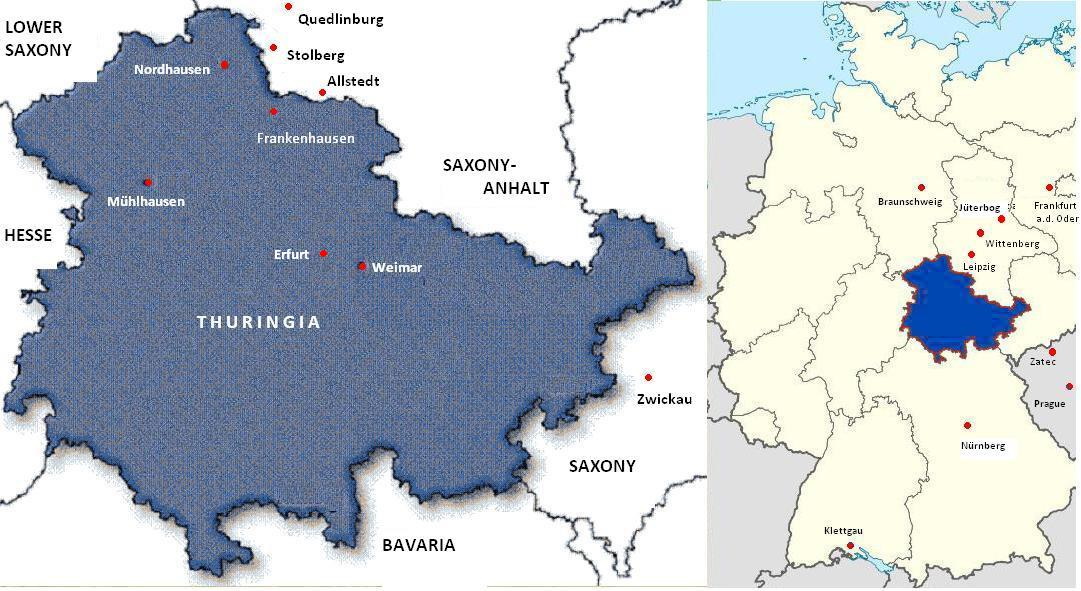

Sketch-map of Thuringia and Germany

For reference, two sketch-maps are provided below, to assist you in identifying the geographical location of places mentioned. To view the maps in a new window, click on the image.

The Müntzer name was known in Stolberg since the 15th century, and various branches of the family were scattered around neighbouring towns and villages. The name would suggest that at some point, ancestors were minters of coins, but this may or may not have been his father's trade. The family probably moved soon after 1490 to the neighbouring and slightly larger town of Quedlinburg, and it was as 'Thomas Munczer de Quedlinburgk' that we next have sight of him, in the university records of Leipzig in 1506. Here he may have studied the Arts or even Theology: alas, Thomas never seems to have actually graduated from Leipzig. But he seems to have made up for that omission by enrolling at the Viadriana University of Frankfurt an der Oder six years later, in 1512. It is not very certain what degrees he may have obtained - almost certainly a Bachelor's degree in Theology and/or the Arts, and possibly - but less certainly - a Master of the Arts. The relevant records are full of holes, or are completely missing. At some time in this rather obscure period of his life, possibly before and during his studies at Frankfurt, he held down posts as an assistant teacher in schools in Halle and Aschersleben, at which time, according to his final confession, he is alleged to have formed a "league" against the incumbent Archbishop of Magdeburg - to what end the league was formed, other than to justify his confessors, is wholly unknown.

The Müntzer name was known in Stolberg since the 15th century, and various branches of the family were scattered around neighbouring towns and villages. The name would suggest that at some point, ancestors were minters of coins, but this may or may not have been his father's trade. The family probably moved soon after 1490 to the neighbouring and slightly larger town of Quedlinburg, and it was as 'Thomas Munczer de Quedlinburgk' that we next have sight of him, in the university records of Leipzig in 1506. Here he may have studied the Arts or even Theology: alas, Thomas never seems to have actually graduated from Leipzig. But he seems to have made up for that omission by enrolling at the Viadriana University of Frankfurt an der Oder six years later, in 1512. It is not very certain what degrees he may have obtained - almost certainly a Bachelor's degree in Theology and/or the Arts, and possibly - but less certainly - a Master of the Arts. The relevant records are full of holes, or are completely missing. At some time in this rather obscure period of his life, possibly before and during his studies at Frankfurt, he held down posts as an assistant teacher in schools in Halle and Aschersleben, at which time, according to his final confession, he is alleged to have formed a "league" against the incumbent Archbishop of Magdeburg - to what end the league was formed, other than to justify his confessors, is wholly unknown.

Günther had already been preaching a reformed gospel, but had found himself viciously attacked by the local Franciscans; requesting leave of absence (probably an early form of professional stress), he left the scene and Müntzer was sent in. The latter picked up where the former had left off, and with added vim. Before long, the local ecclesiastics were complaining bitterly about Müntzer's heretical 'articles' which challenged both church teaching and church institutions.

By this time, Müntzer was not merely following Luther's teachings; he had already begun to read the teachings of the mystics Suso and Tauler, was seriously wondering about the possibility of enlightenment through dreams and visions, had thoroughly explored the early history of the Christian Church, and was in contact with other, more radical, reformers such as Karlstadt.

Günther had already been preaching a reformed gospel, but had found himself viciously attacked by the local Franciscans; requesting leave of absence (probably an early form of professional stress), he left the scene and Müntzer was sent in. The latter picked up where the former had left off, and with added vim. Before long, the local ecclesiastics were complaining bitterly about Müntzer's heretical 'articles' which challenged both church teaching and church institutions.

By this time, Müntzer was not merely following Luther's teachings; he had already begun to read the teachings of the mystics Suso and Tauler, was seriously wondering about the possibility of enlightenment through dreams and visions, had thoroughly explored the early history of the Christian Church, and was in contact with other, more radical, reformers such as Karlstadt. Amongst the weavers this movement was particularly strong. Taboritism, and also spiritualism. One Nikolaus Storch was active here, a self-taught radical who placed every confidence in spiritual revelation through dreams. Soon he and Müntzer were eyeing each other up as likely allies. In the following months, Müntzer found himself more and more at odds with Egranus, the nominal representative of the Wittenberg movement, and increasingly embroiled in all manner of uproar against the local Catholic priests. The town council became nervous at what was going on at St Katharine's, and on 16 April 1521 at last decided that enough was enough: Müntzer was dismissed from his post and was forced to leave Zwickau.

Amongst the weavers this movement was particularly strong. Taboritism, and also spiritualism. One Nikolaus Storch was active here, a self-taught radical who placed every confidence in spiritual revelation through dreams. Soon he and Müntzer were eyeing each other up as likely allies. In the following months, Müntzer found himself more and more at odds with Egranus, the nominal representative of the Wittenberg movement, and increasingly embroiled in all manner of uproar against the local Catholic priests. The town council became nervous at what was going on at St Katharine's, and on 16 April 1521 at last decided that enough was enough: Müntzer was dismissed from his post and was forced to leave Zwickau.

An initial scouting expedition took Müntzer over the border into Bohemia to the town of Zatec (Saaz) - this town was known as one of the five "safe citadels" of the radical Taborites of Bohemia. However, Müntzer decided that his next port of call would be Prague. It was in Prague that the Hussite Reformed Church was already firmly established and here, no doubt, that Thomas thought to find a safe haven where he could develop his increasingly un-Lutheran ideas. Possibly not far from his thoughts was the fact that, in that summer, the Ottoman armies were moving steadily through Hungary - thereby signalling the End of Time. He arrived in Prague in late June of 1521. He was made welcome since he was perceived to be what he was not - a follower of Luther - and was allowed to preach and to give lectures at the University. He also found the time to prepare a summary of his own beliefs, which appeared in what became known as the `Prague Manifesto'. This document exists in four forms - one in Czech, one in Latin, two in German; one of them is written on a large piece of paper, about 50cm square, like a poster. It is almost certain that none of the four items was ever published or posted in any shape or form. But it is clear from this document just how far he had diverged from the road of the Wittenberg reformers, and how much he believed that the reform movement was something apocalyptic in nature.

An initial scouting expedition took Müntzer over the border into Bohemia to the town of Zatec (Saaz) - this town was known as one of the five "safe citadels" of the radical Taborites of Bohemia. However, Müntzer decided that his next port of call would be Prague. It was in Prague that the Hussite Reformed Church was already firmly established and here, no doubt, that Thomas thought to find a safe haven where he could develop his increasingly un-Lutheran ideas. Possibly not far from his thoughts was the fact that, in that summer, the Ottoman armies were moving steadily through Hungary - thereby signalling the End of Time. He arrived in Prague in late June of 1521. He was made welcome since he was perceived to be what he was not - a follower of Luther - and was allowed to preach and to give lectures at the University. He also found the time to prepare a summary of his own beliefs, which appeared in what became known as the `Prague Manifesto'. This document exists in four forms - one in Czech, one in Latin, two in German; one of them is written on a large piece of paper, about 50cm square, like a poster. It is almost certain that none of the four items was ever published or posted in any shape or form. But it is clear from this document just how far he had diverged from the road of the Wittenberg reformers, and how much he believed that the reform movement was something apocalyptic in nature.

It was the Elector Friedrich himself who held the right to appoint to St John's, but the town-council either forgot to inform him, or did not feel his approval was necessary. Almost immediately on arrival, Müntzer was busy preaching his version of the reformed doctrines, and translating the standard church services and mass into German. Such was the popularity of his preaching, and the novelty of hearing the services being held in German, that people from the surrounding countryside and towns were soon flocking to Allstedt - some reports suggest that upwards of two thousand people were on the move every Sunday.

Within weeks, Luther got to hear of this and he was soon writing to the local tax-collector, Hans Zeiss, asking him to persuade Müntzer to come to Wittenberg for closer inspection. Müntzer refused to go. He was far too busy carrying through his Reformation and wanted no discussion 'behind closed doors'. As part of his reforms, perhaps, he married Ottilie von Gersen, a former nun; in the Spring of 1524, Ottilie gave birth to a son.

It was the Elector Friedrich himself who held the right to appoint to St John's, but the town-council either forgot to inform him, or did not feel his approval was necessary. Almost immediately on arrival, Müntzer was busy preaching his version of the reformed doctrines, and translating the standard church services and mass into German. Such was the popularity of his preaching, and the novelty of hearing the services being held in German, that people from the surrounding countryside and towns were soon flocking to Allstedt - some reports suggest that upwards of two thousand people were on the move every Sunday.

Within weeks, Luther got to hear of this and he was soon writing to the local tax-collector, Hans Zeiss, asking him to persuade Müntzer to come to Wittenberg for closer inspection. Müntzer refused to go. He was far too busy carrying through his Reformation and wanted no discussion 'behind closed doors'. As part of his reforms, perhaps, he married Ottilie von Gersen, a former nun; in the Spring of 1524, Ottilie gave birth to a son.

Throughout the balance of 1523, and into 1524, Müntzer was employed in consolidating his reformed services and teachings in the small town. He also found the time to arrange for the printing of his German Church Service and two tracts, the Protestation or Petition by Thomas Müntzer from Stolberg in the Harz Mountains, now Pastor of Allstedt, about his teachings, beginning with true Christian faith and baptism and On Fraudulent Faith, in which he set out his doctrine that the true faith came from inner spiritual suffering and despair.

Throughout the balance of 1523, and into 1524, Müntzer was employed in consolidating his reformed services and teachings in the small town. He also found the time to arrange for the printing of his German Church Service and two tracts, the Protestation or Petition by Thomas Müntzer from Stolberg in the Harz Mountains, now Pastor of Allstedt, about his teachings, beginning with true Christian faith and baptism and On Fraudulent Faith, in which he set out his doctrine that the true faith came from inner spiritual suffering and despair.

Mühlhausen was a town with a population of 8500. During 1523 social tensions which had been brewing for several years came to a head, and the inhabitants had managed to wrest some political concessions from the elitist town-council; building on this success, the radical reform movement kept up the pressure, under the leadership of a lay-preacher named Heinrich Pfeiffer, who had been denouncing the practices of the old Church from the pulpit of St Nikolaus Church. Thus, before Müntzer arrived here, there was already considerable tension in the air. This, however, did not stop Müntzer from doing what he did best - preaching, agitating and publishing inflammatory pamphlets against Luther. His comrade-in-arms here was Pfeiffer; while the two men did not necessarily share identical beliefs, there was enough common-ground in the matter of reformatory zeal and belief in the living divine spirit to allow them to work together closely. A miniature coup took place in late September 1524, as a result of which leading members of the town-council fled the town, taking with them the city insignia and the municipal horse. But the coup was short-lived - partly because of divisions within the reformers inside the town, and partly because the peasantry in the surrounding countryside took issue with the 'unchristian behaviour' of the radicals. After only seven weeks in the town, on 27th September, Müntzer was forced to abandon wife and child once more and escape to a safer haven.

Mühlhausen was a town with a population of 8500. During 1523 social tensions which had been brewing for several years came to a head, and the inhabitants had managed to wrest some political concessions from the elitist town-council; building on this success, the radical reform movement kept up the pressure, under the leadership of a lay-preacher named Heinrich Pfeiffer, who had been denouncing the practices of the old Church from the pulpit of St Nikolaus Church. Thus, before Müntzer arrived here, there was already considerable tension in the air. This, however, did not stop Müntzer from doing what he did best - preaching, agitating and publishing inflammatory pamphlets against Luther. His comrade-in-arms here was Pfeiffer; while the two men did not necessarily share identical beliefs, there was enough common-ground in the matter of reformatory zeal and belief in the living divine spirit to allow them to work together closely. A miniature coup took place in late September 1524, as a result of which leading members of the town-council fled the town, taking with them the city insignia and the municipal horse. But the coup was short-lived - partly because of divisions within the reformers inside the town, and partly because the peasantry in the surrounding countryside took issue with the 'unchristian behaviour' of the radicals. After only seven weeks in the town, on 27th September, Müntzer was forced to abandon wife and child once more and escape to a safer haven.

He went first, by circuitous route, to Nürnberg in the south, where he arranged, through third-parties, the publication of his anti-Lutheran pamphlet A Highly Provoked Speech of Defence and Answer to the Spiritless Easy-Living Flesh in Wittenberg, as well as one entitled Explicit Exposure of the False Belief - both of which, unfortunately, were confiscated by the city authorities before too many copies could be distributed. Müntzer himself lay low in Nürnberg, considering that his best strategy would be to get into print, rather than end up in prison. He remained here until late November and then left for the south-west of Germany and Switzerland, where peasants and plebeians were organising themselves for the great 'Peasant War' of 1524/25 in defiance of their feudal overlords. There is no direct evidence of what Müntzer did in this part of the world, but almost certainly he would have come in contact with leading members of the various rebel conspiracies; it is proposed that he met the later Anabaptist leader, Balthasar Hubmaier in Waldshut, and it is known that he was in Basel in December, where he met the Zwinglian reformer Oecolampadius, and may also have met the Swiss Anabaptist Conrad Grebel there. He spent several weeks in the Klettgau area, and there is some evidence to suggest that he helped the peasants to formulate their grievances. While the famous 'Twelve Articles' of the Swabian peasants were certainly not composed by Müntzer, at least one important supporting document, the Constitutional Draft (Verfassungsentwurf), may well have originated with him. In any event, it is probable that what he saw taking place here - peasants on the march, demands for democracy - inspired him to return to his old stomping-ground and set the cause afoot once more.

He went first, by circuitous route, to Nürnberg in the south, where he arranged, through third-parties, the publication of his anti-Lutheran pamphlet A Highly Provoked Speech of Defence and Answer to the Spiritless Easy-Living Flesh in Wittenberg, as well as one entitled Explicit Exposure of the False Belief - both of which, unfortunately, were confiscated by the city authorities before too many copies could be distributed. Müntzer himself lay low in Nürnberg, considering that his best strategy would be to get into print, rather than end up in prison. He remained here until late November and then left for the south-west of Germany and Switzerland, where peasants and plebeians were organising themselves for the great 'Peasant War' of 1524/25 in defiance of their feudal overlords. There is no direct evidence of what Müntzer did in this part of the world, but almost certainly he would have come in contact with leading members of the various rebel conspiracies; it is proposed that he met the later Anabaptist leader, Balthasar Hubmaier in Waldshut, and it is known that he was in Basel in December, where he met the Zwinglian reformer Oecolampadius, and may also have met the Swiss Anabaptist Conrad Grebel there. He spent several weeks in the Klettgau area, and there is some evidence to suggest that he helped the peasants to formulate their grievances. While the famous 'Twelve Articles' of the Swabian peasants were certainly not composed by Müntzer, at least one important supporting document, the Constitutional Draft (Verfassungsentwurf), may well have originated with him. In any event, it is probable that what he saw taking place here - peasants on the march, demands for democracy - inspired him to return to his old stomping-ground and set the cause afoot once more.

At that time too, however, the princes were laying their own plans for the suppression of the revolt. Unfortunately, the feudal authorities had far better arms and far greater discipline than their subjects. At the beginning of May, the peasant-plebeian rebels marched around the countryside in north Thuringia, but failed signally to meet up in any sensible way with other troops, being content to loot and pillage locally.

At that time too, however, the princes were laying their own plans for the suppression of the revolt. Unfortunately, the feudal authorities had far better arms and far greater discipline than their subjects. At the beginning of May, the peasant-plebeian rebels marched around the countryside in north Thuringia, but failed signally to meet up in any sensible way with other troops, being content to loot and pillage locally.

These others, however, were not always warned. During the last two years of his life, Müntzer had come into contact with a number of other rebellious spirits - prominent amongst them were Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Melchior Rinck, Hans Römer and Balthasar Hubmaier: all of them, leaders of the nascent Anabaptist movement, which nurtured similar radical reform doctrines to those of Müntzer himself. While it is not appropriate to claim that they were all or consistently 'Müntzerites', it is reasonable to suggest that they all took on board some of his teaching. Even within the towns where Müntzer had been active, his reformed liturgies were still being used some ten years after his death, much to Luther's horror. Through the Anabaptists, a line leads from Müntzer to the extraordinary 'Kingdom of Münster' in North Germany in 1535, to the Dutch Anabaptists, to the English radicals of the mid-17th century, and beyond. It is not far-fetched to claim that Müntzer was the giant on whose shoulders other giants then stood, in a line stretching down across centuries to the socialists of the 19th and 20th centuries: it was thus that Engels and Kautsky claimed him as a precursor of the revolutionaries of more modern times. But it is not solely as an early social revolutionary that Müntzer has historical importance; his activities within the early Reformation church were - although Luther would have been the last to admit it - highly influential on the course which Luther subsequently took for his reforms.

These others, however, were not always warned. During the last two years of his life, Müntzer had come into contact with a number of other rebellious spirits - prominent amongst them were Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Melchior Rinck, Hans Römer and Balthasar Hubmaier: all of them, leaders of the nascent Anabaptist movement, which nurtured similar radical reform doctrines to those of Müntzer himself. While it is not appropriate to claim that they were all or consistently 'Müntzerites', it is reasonable to suggest that they all took on board some of his teaching. Even within the towns where Müntzer had been active, his reformed liturgies were still being used some ten years after his death, much to Luther's horror. Through the Anabaptists, a line leads from Müntzer to the extraordinary 'Kingdom of Münster' in North Germany in 1535, to the Dutch Anabaptists, to the English radicals of the mid-17th century, and beyond. It is not far-fetched to claim that Müntzer was the giant on whose shoulders other giants then stood, in a line stretching down across centuries to the socialists of the 19th and 20th centuries: it was thus that Engels and Kautsky claimed him as a precursor of the revolutionaries of more modern times. But it is not solely as an early social revolutionary that Müntzer has historical importance; his activities within the early Reformation church were - although Luther would have been the last to admit it - highly influential on the course which Luther subsequently took for his reforms.